The Chinese Must Go

Violence, Exclusion and the Making of the Alien in America

Beth Law-Williams 2018 349 pages (244 w/o index and appendices)

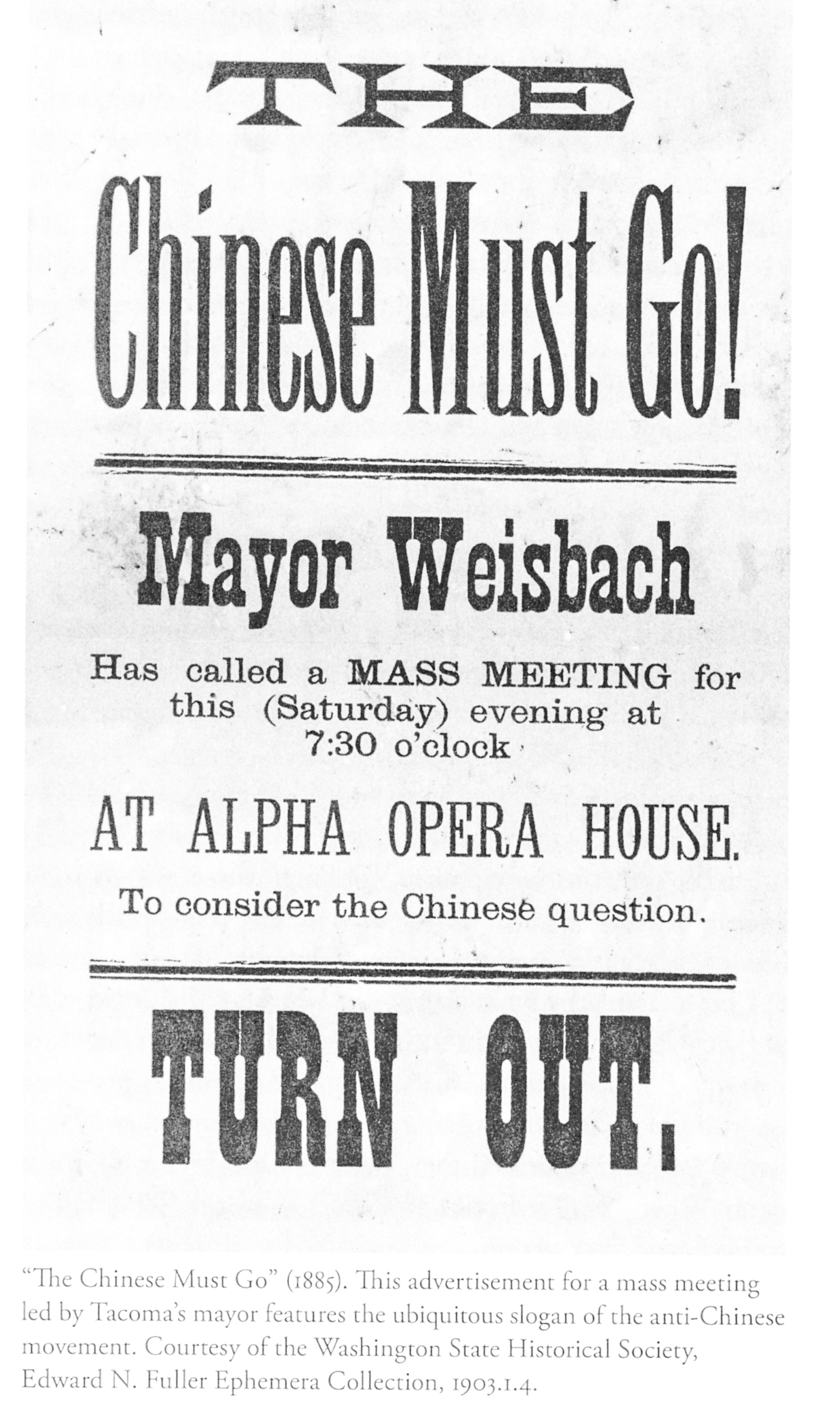

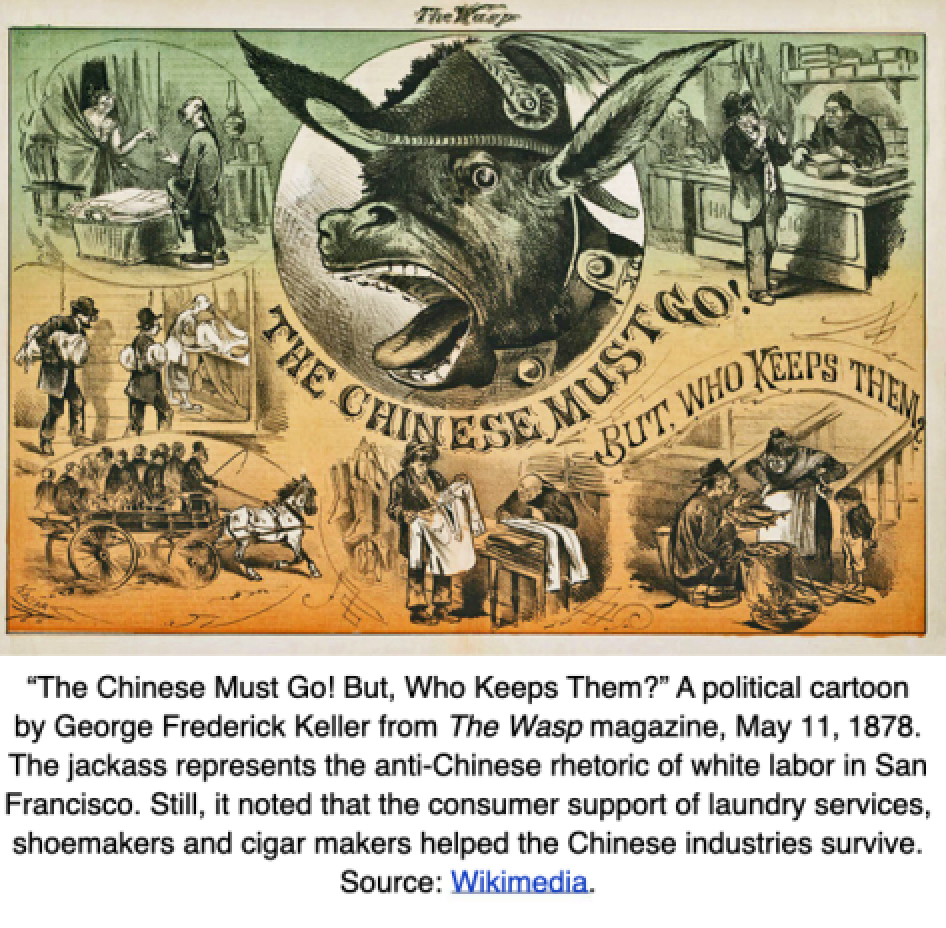

See book cover in 3/25 and pol cartoon from the wasp in the ditches book also a flyer

This book is about an unsavory episode in American history. The first couple of sentences in the introduction tell us what’s coming,

“They left in driving rain. Three hundred Chinese migrants trudged down the center of the street, their heads bowed to the elements and the crowd. They were led, followed, and surrounded by dozens of white men armed with clubs, pistols, and rifles. As if part of a grim parade, they were encircled by spectators who packed the muddy sidewalks, peered from narrow doorways, and leaned out from second story windows… [the mob yelled], All the Chinese, you must go. Everyone.”

Imagine.

That was Tacoma, Washington in 1885 but the scene was repeated with slight differences in all the west coast states. The book doesn’t cover it but the prejudice reached to Truckee and even Donner Summit – see below.

Why the prejudice? “While white citizens worried that Native Americans and Africans Americans would contaminate the nation, they feared the Chinese might conquer it. One anti-Chinse leader in Tacoma, for example, openly worried that if ‘millions of industrious hardworking sons and daughters of Confucius’ were ‘given an equal chance with our people,’ they ‘would outdo them in the struggle for life and gain possession of the pacific coast of America.”

Books like this are one of the reasons we study history – so we don’t repeat the same mistakes and so we understand our past.

The book tells the story of the anti-Chinese discrimination in three parts: I, the rise of restrictive acts to discriminate against the Chinese; II, three viewpoints of the discrimination and the various ways it was carried out in various places; and III, the many Federal policies that followed and codified discrimination in law and treaty.

In the first part there are many anecdotes and quotes portraying the discrimination and even the supporting philosophy. When the Chinese were ordered to leave Port Madison, “the newspaper did not report the expulsion as an act of violence, or even as a crime. Instead, it was ‘a solution’ to the problem of Chinses Labor…” A few sentences later another sentence explains a little more, “To white observers, the value of Chinese lives was o little, and the violence against them so abundant, that most forms of harassment seemed unremarkable.”

No one recorded how the Chinese felt at the time but decades later researchers recorded their feelings, “Oh, it was terrible, terrible. At the time all Chinese have queue and dress same as in China, The hoodlums, rough necks and young boys pull you queue, slap our face, [throw] all kind of old vegetables and rotten eggs at you. All you could do was run and get out of the way.” Imagine living through that and then having your livelihood and property taken away. The book gives the reader an unvarnished view of how America’s western states dealt with the “Chinese problem” and the use of many quotes and anecdotes humanizes the effects on the Chinese.

There’s a long list of examples of discrimination in the first part which essentially present the thinking of many Americans: “How would a government of the people and by the people endure if those people were incapable of assimilation and self-government? If the Chinese became U.S. citizen, Dooner’s (see the sidebar here) dystopia would be close at hand” i.e. the Chinese would take over.

The prejudice wasn’t just held buy a small part of the population. 99% of California voters, on an 1879 ballot, were against Chinese immigration.

The prejudice led to laws restricting the Chinese entry to the U.S., violations of the 14th Amendment , demagoguery and violence. One senator, in support of a law against citizenship for Chinese said, “Do you want to have the Chinese slaughtered on the Pacific Coast… Do you want their extermination?” That would no doubt happen if the law allowing citizenship were passed. He continued, the West would be “overpowered by the mob elements that seek to exterminate the Chinese” and “they will be slaughtered before anyone of them can be naturalized.”

It’s disheartening to see the various forms of prejudice, imagine their effects, and see people trying to support their discriminatory views. Maybe it wasn’t so great and the “good old days.”

The second part of the book describes the violence and again there are lots of examples and quotes from both sides. The wife of the governor of Washington, for example, described going down to the wharf where Chinese were being put on ships to be taken away. This was the “vigilantes’ triumph.” “three hundred [Chinese] were crowded on the wharf – trembling and crying” “Poor things…how cruel.” Then she went about her business. Portland merchants described another expulsion, “The suffering was beyond description… Their cries could be heard miles away.”

Imagine the experiences of those people. Where were they going to go? How would they start new lives?

Violence bred violence and there was justification in some people’s minds, “Chinese migration posed an existential threat to white settlement in the U.S. West. The federal government had failed do protect American citizens from imminent danger,.. rendering the massacre justifiable. It was an act of preemptive self-defense.” Violence became normalized. “If the government could not or would not save the West Coast from alien invaders, …the white people of the West Coast had to take the law into their own hands.” “…people had the right to rebel when federal policies endangered the nations’ welfare.”

It’s interesting that of course not everyone was against the Chinese but many who were not hoped that the boycotts of Chinese, another way of driving them out, would reduce the violence. That way the reality of vigilante violence could be avoided. Driving out the Chinese would make things safer. Of course how would do the work?

The last part of the book goes into the Federal Government’s responses passing anti-Chinese laws and developing treaties with China to restrict immigration. Again there are lots of examples and that gets tedious: all the details going into the laws and writing the treaties. Lots of people had lots to say in enacting things. We do get into the minds of 19th Century Americans, for example, “the Chinese people’s ‘barbaric’ and ‘heathen’ customs, such as polygamy and Confucianism, made it clear to Western nation that they could not be classified as civilized. And, by defining Chinese as ‘uncivilized,’ Western nations gave themselves license to establish indirect control over the weak Chinese state.”

The Chinese were expelled from many places leaving the question of where did they go? The Central Valley of California absorbed many because there was so much agricultural labor needed. Other Chinese went to accepting urban areas like San Francisco and Los Angeles. Others went abroad.

At the end the author talks about the effects of anti-Chinese campaigns: lost businesses, lost lives, loss of a sense of security, stigma, shame, degradation, homelessness, etc. There was the wider set of consequences too: more smuggling of Chinese into California, a change in the racial divide and “rules”, and more Asian exclusion of other groups.

It’s a sobering book